How do you handle research?

Debut authors delve into the research than drove their historical fiction!

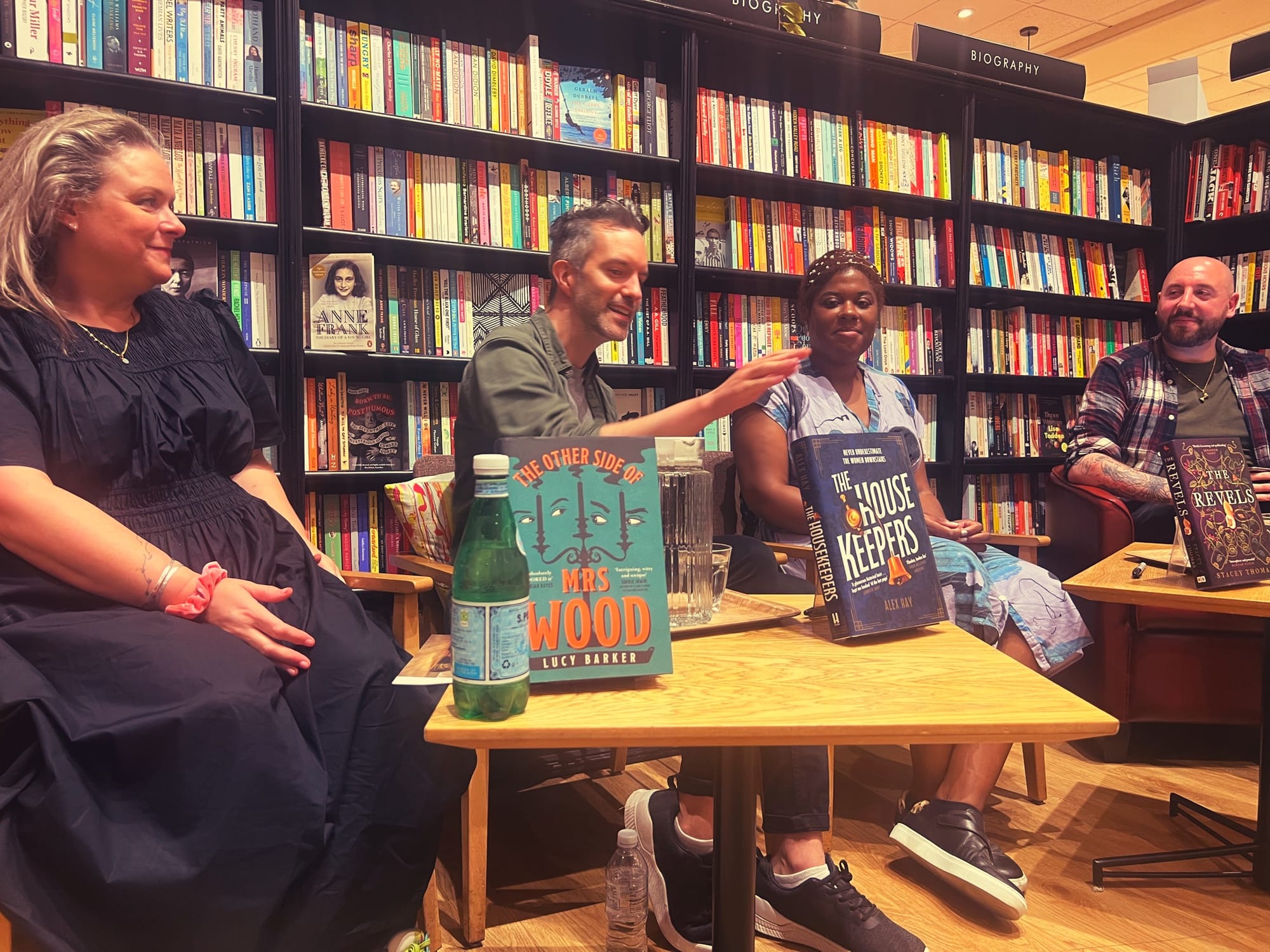

Last week, I had the pleasure of attending a debut author event at Waterstone’s Bristol with my wife, Clare. On the panel were historical novelists Lucy Barker, Alex Hay and Stacey Thomas, all of whom have written intriguing new novels:

🕯️ The Other Side of Mrs Wood - a tale of warring 19th-century mediums.

⏱️ The Housekeepers - described as Upstairs Downstairs meets Ocean’s 11. (Yes please!)

🐁 The Revels - the story of a witchfinder who unwittingly hires a witch as their apprentice.1

It’s always interesting to hear how writers differ from each other. For example, Alex planned out The House Keepers in exhaustive detail, plotting everything out in what he called his ‘spreadsheet of doom’, while Lucy admitted she is a complete ‘pantser2’, making it up as she goes along. If she makes a detailed plan, the story loses all excitement for her.3 This is compounded by the fact that she’s a sprint writer, writing in a flurry without going back to edit until the end.4

The conversation became most interesting when it focused on research, appropriate for a group of historical novelists!5 Stacey proved herself to be the Queen of research within the group, which makes sense as she studied history at University. Writing The Revels generated a staggering 800 pages of research over lockdown, which she eventually whittled down to 200 pages of facts and figures that were useful. She admitted that she regularly uses research as a form of procrastination. Even though, that’s impressive! It’s fair to say the other writers were equally flabbergasted at the sheer scale of her endeavour!

Alex, on the other hand, said he uses research to pause during the writing process. The example he gave was when one of his characters needed to use the London Underground. Was there even a tube in 1905, he asked himself, and where did it run? And, if there was, how much was a ticket from Marble Arch to Pall Mall?6 He stopped writing, plugged into a little light research before heading back to the story.

Research also brought surprises for Alex, who said he didn’t realise just how much corruption there really was when you scratch the gilded surface of early 19th Century London, especially targeted against young female servants. But there were also delightful discoveries to be made, such as the fact that the most progressive houses at the turn of the century (at least in terms of technology) had ‘electroliers’ instead of ‘chandeliers’ thanks to the invention of the electric lightbulb. Lovely little titbits like this add colour and specificity to a setting.

The trick is to give readers enough detail to give the story authenticity

without bogging down the action.

But research can also become a hindrance, as Lucy illustrated by discussing the importance of including accurate details without becoming overtly bound to the facts. This doesn’t mean the details in Mrs Wood are incorrect — Lucy was keen to point out that every time weather is mentioned in the book it is actually what was metrologically recorded for the date in question — but that doesn’t mean that she was writing non-fiction. The trick is to give readers enough detail to give the story authenticity without bogging down the action. And, at the end of the day, creative licence is allowed! The key is for your research to help set the tone of the story, not to deliver a lecture. In fact, at one point, Lucy’s editor asked for more ‘tricks of the trade’ to sell the seances that appear in the novel, which Lucy duly supplied in the second draft, only to be instructed to take them all out again because they slowed everything down!

As someone who primarily writes licenced fiction, I found all of this deeply fascinating. I always compare it to historical research, especially if you’re writing for something that has been around for forty-plus years like Star Wars. There’s a whole library of books, comics, shows and movies out there and, while you can’t always read or see everything, you need to make sure you know the basics as there are plenty of fans out there who know much more than you. I had a head start with both Star Wars and Doctor Who, having been a fan since I was knee-high to an Ewok, but when it came to something like Warhammer 40,000, well, I had to go back to school.

Yes, there are editors and lore-keepers, like Lucasfilm’s story group, but you need to do your homework to make sure you don’t drop a Millennium Falcon-sized clanger that will drag the reader or viewer out of the story.

There’s something else I’ve discovered about research. Sometimes, it digs up facts that are one-hundred-percent true, but the audience will find hard to swallow. An example came while writing my second Sherlock Holmes novel, Cry of the Innocents. Much of the action takes place in a hotel based on the Marriot Royal in Bristol. In the book, my version of the hotel has a female manager. My editor told me this just wasn’t believable in a story set at the end of the 19th Century. The only trouble is that the character was based on the Royal’s very real female manager who held the position, you guessed it, at the end of the 19th Century. There was a lot of back and forth on that one, and eventually my female manager stayed in her post, despite the editor’s fears that 21st Century readers wouldn’t accept that a woman would hold such a position back then. But as Dan Bassett, the moderator of last Wednesday’s event, pointed out, sometimes we read historical fiction to learn something as well!

But what about you? How do you research for your stories? And for the readers among you, how important is it for you to know that the writer has done their due diligence? How willing are you to turn a blind eye to the facts for the sake of a story, or do you want everything to be exactly right?

Let us know in the comments!

And yes, we came away with signed copies of all three novels! Now, the question is which to read first. Well, Alex’s The House Keepers has shot to the top of my TRP, while Clare is opting for The Revels. We will read all three, though! ↩

Pantser is a phrase coined by Stephen King to describe his method, starting at the beginning and writing ‘by the seat of one’s pants’ until you reach the ending, which you discover on the way. I’m a planner, but that has a lot to do with the amount of IP writing I do. There’s no getting away from outlines in licenced work as you need to have every signed off by the license holder before you start writing! ↩

Interestingly, Alex shared that when tackling his second novel, he again created a spreadsheet of doom, but this time found the process stifling. Different books sometimes call for different methods! ↩

She’s not alone. This is how I work once I have an outline, splurging everything onto the page so I can go back and tidy up later. Last week was a sprint for me but on an audio script rather than a novel. I set myself the challenge of 4,000 words daily to get 20k in the tank. I managed it, but I dread to think what state the script is in! Sprint writers often have to do a LOT of editing! ↩

Hmmm. What is the collective noun for historical writers? A study? A research? A quill? ↩

Alex mentioned a — rather snotty — early review that claimed there couldn’t possibly be an underground station at the time the story was set, even though his research proved otherwise. It reminded me of the time a reviewer questioned the barriers at a particular underground station in my buddies Mark Wright and Mike Collin’s Doctor Who comic, The Highgate Horror. “But the barriers didn’t exist in the early 1970s, so the Doctor couldn’t possibly have jumped over them!” the reviewer bleated until Mike pulled out the reference photo he’d used…from the early 1970s! What is it about the London Underground that brings out the ‘I think you’ll find’ squadron?! ↩